How 2,420 Russian Starlink Terminals Just Became Digital Targets

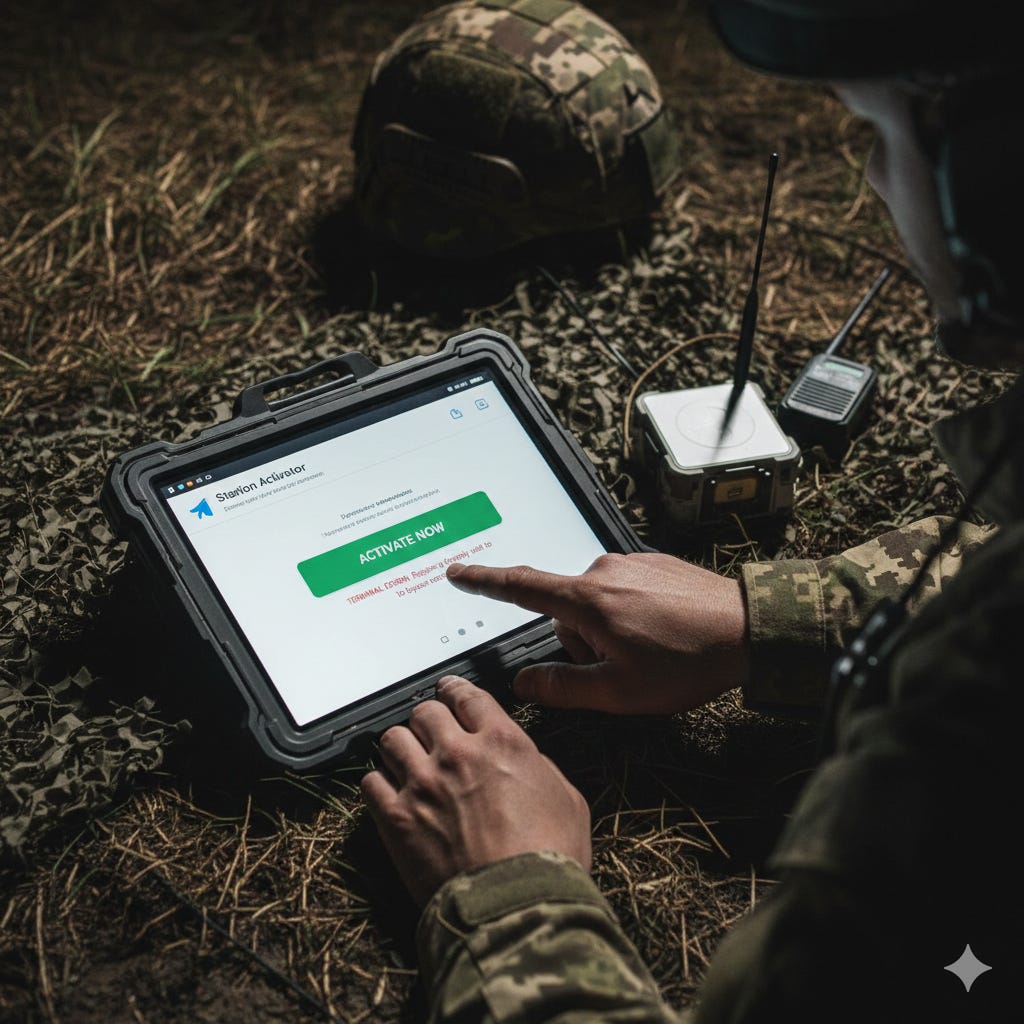

It wasn't a missile that blinded the Russian drone teams in Zaporizhzhia this week. It was a QR code and a Telegram bot.

When SpaceX and the Ukrainian government finally pulled the plug on unauthorized Starlink terminals used by Russian forces, the frontline went dark. Communications collapsed, drone feeds flickered out, and Russian units—desperate to restore the one Western technology they can’t live without—started looking for a workaround.

They found one. Or so they thought.

The “Activation” Trap

Ukrainian hacktivists from the 256th Cyber Assault Division, working alongside InformNapalm, didn’t just wait for the Russians to scramble; they built the net.

They launched a network of fake Telegram channels and “activation bots” promising a way to bypass the new Ukrainian “whitelist” registration system. For a modest fee, the bots promised to register illicit terminals under “safe” Ukrainian identities, keeping the dishes online.

The Russians took the bait. In less than seven days:

2,420 data packages were harvested, containing serial numbers and precise GPS coordinates of Russian Starlink terminals.

$5,870 in “fees” was siphoned directly from Russian soldiers’ pockets into funds for the Ukrainian Defense Forces.

31 local collaborators (potential “drops”) were identified and handed over to law enforcement.

From “Online” to “Brick Mode”

The operation didn’t just harvest data—it weaponized it. The 256th Division confirmed they passed the technical identifiers to Ukrainian drone logistics advisor Serhiy Sternenko.

The goal? “Brick Mode.” By identifying the exact digital signatures of the terminals being used by the enemy, Ukraine and SpaceX can remotely disable the hardware permanently. But before the “kill switch” is flipped, those GPS coordinates are being used for something much more immediate: kinetic strikes. In the world of electronic warfare, if you can see the terminal, you can see the command post.

The Fatal Breach: Why OPSEC is Must

In the intelligence community, there is a saying: “The easiest way to get into a locked building is to have the owner open the door.” This operation succeeded because Russian frontline units prioritized immediate tactical convenience over long-term Operational Security (OPSEC).

By engaging with unverified third-party bots to register military hardware, Russian forces violated the most fundamental rules of digital warfare:

Trusting the “Grey Market”: In a conflict zone, there is no such thing as a “friendly” unauthorized service. By seeking a workaround for SpaceX’s restrictions, the users handed their hardware’s unique identifiers directly to the adversary.

GPS as a Weapon: A Starlink terminal is a beacon. By attempting to “spoof” location data through an unsecure bot, the operators inadvertently confirmed their exact positions. In the age of precision artillery, Location Data = Targeting Data.

The “Convenience Trap”: The desire to maintain a high-bandwidth connection for drone feeds created a psychological blind spot. The 256th Division exploited the “user experience” of a soldier—making the fake bot look and feel like a standard service—to bypass their survival instincts.

CodeAintel Warning: OPSEC isn’t just about hiding secrets; it’s about managing the digital footprint of your hardware. When a soldier treats a military comms device like a personal smartphone, they aren’t just compromised—they are categorized and neutralized.

Technical Brief: The Link Between Identity and Location

For a Starlink terminal to function, it must maintain a constant handshake with the satellite constellation. This process creates a “Digital ID” that is nearly impossible to fake once it is flagged:

Terminal ID (Hardware SN): Each dish has a unique serial number burnt into its hardware.

GNSS Integration: Every terminal contains a GPS/GNSS module to orient its phased-array antenna.

The Handshake: SpaceX sees which Serial Number is requesting data from which GPS Coordinate.

By submitting their SN to the fake Ukrainian bot, the Russian operators essentially signed their own death warrants, allowing the SBU to cross-reference that ID with active satellite pings.